Neo Nazis are again on the march in Australia. The National Socialist Network is looking more professional than previous scrofulous iterations; showing effective marketing smarts with social media member recruitment and merchandise*, and bureaucratic smarts by getting police approval of their public demonstrations. NSN membership qualification is said to include reading of Hitler’s Mein Kampf.

(*using Helly Hansen spray jackets, as HH initials could stand for Heil Hitler)

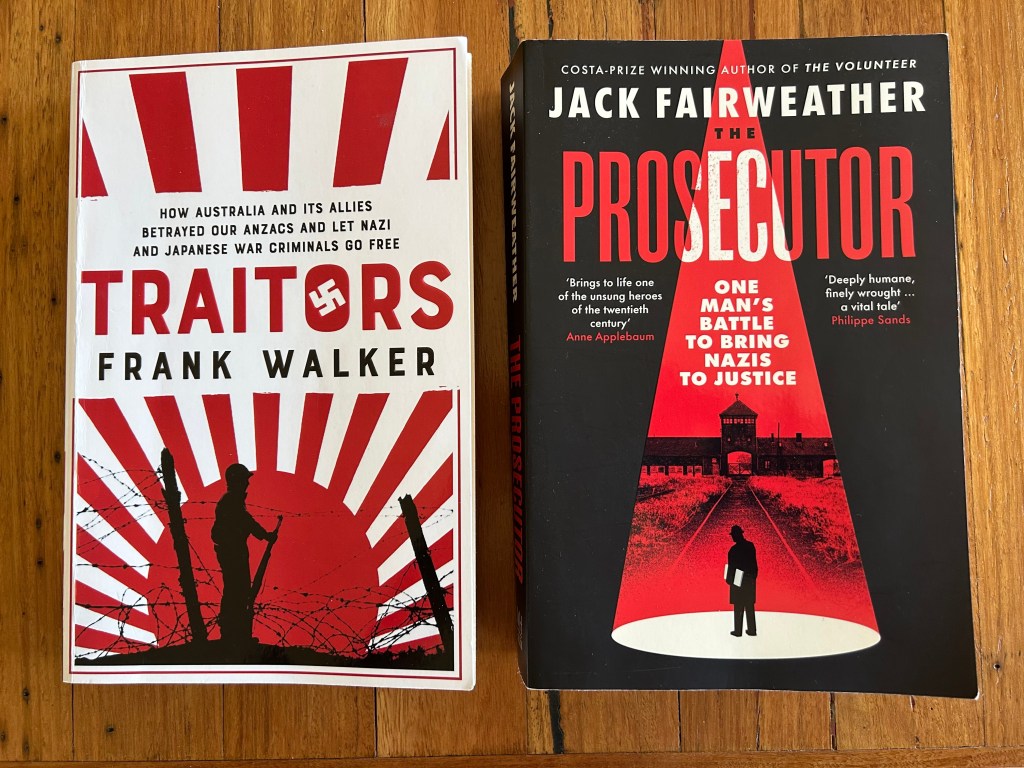

With that background, two books about post-WW2 attempts at judicial reckoning of Nazi and Japanese war criminals may be of interest. They recount the challenges of public resistance, official prevarication and political obfuscation in Germany, Japan and even Australia.

THE PROSECUTOR by Jack Fairweather, subtitled One Man’s Battle to Bring Nazis to Justice, was published this year, and is an engrossing reconstruction of the life of Fritz Bauer, a gay Jewish German lawyer who fought hard and fearlessly against the odds.

From Ludwigsburg near Stuttgart, Bauer was a high profile, progressive social democrat activist during the Weimar years, who spoke out at rallies against the rise of Hitler. Recognised as a troublemaker and persecuted by the Nazis, he managed to flee to Copenhagen in 1936.

In exile he researched legal theory and historical practices around international war crimes, publishing a book War Criminals on Trial in 1944, in anticipation of his return to Germany ‘to confront the people who had attempted the industrialised murder of Europe’s Jews’.

Bauer had a leading role in preparation of prosecution cases at the Nuremberg trials of high-ranking Nazi leaders, but he was also determined to pursue lower level officials involved in concentration camp and other mass killings; and force post-war German society to reckon with their own complicity. Legal obstacles and official inertia were considerable. Political consensus was to bury the past.

Adolf Eichmann’s ex deputy Hans Globke became state secretary under new German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, and helped the post war government’s effort to ‘let bygones be bygones’. An overwhelming vote in the Bundestag in December 1949 ended the denazification program and approved general amnesty for offences committed during the war. Almost 800,000 people with light sentences were pardoned, including 30,000 war criminals.

The story of Bauer’s efforts over twenty five years to wrangle state judicial systems and his heroic life as a gay public official is inspiring. However soon after his death in 1968 ‘German legislation time-barring prosecution of Nazi crimes came into force, limiting courts to trying cases only where murderous intent could be proven’. Fairweather says the ‘vast majority’ of Germans who had helped in the Final Solution were not pursued, with 282 former Nazis cases dropped that year.

Fairweather also concludes that Bauer’s relentless legal and public relations campaigns for collective reckoning inspired a new generation of jurists, activists, writers and educators:

‘From the forty-seven words devoted to the Final Solution in the textbooks of 1956, the subject steadily expanded throughout the 1970s to dominate the teaching of modern German history. The growth in knowledge led to a quiet moral awakening that was bolstered by increasing depictions of Nazi atrocities in books and film. In 1979, twenty million West Germans – half the adult population – watched the American miniseries Holocaust about a fictional Jewish family in Berlin starring Meryl Streep. Thousands called in to an accompanying hotline staffed by historians to express outrage at their own country.’

‘Germany’s reckoning with Nazism has exceeded some of Bauer’s expectations, but he would also have been troubled by the silence and shame that persist within German households with connections to Nazis’.

‘A 2014 study found that only 1 percent of Germans polled believed their own families had been active supporters of Nazism. Two contradictory narratives seem to exist for these children and grandchildren of the war generation. They recognise the Holocaust as a national crime. But they cannot reconcile its horrors with the picture they hold of their family members – or of themselves.’

As the war ended, the US government was also complicit in burying the German past as it prioritised the fight against Soviet communist influence there, and even set up a spy network in Germany using ex Nazis under leadership of Reinhard Gehlen, Hitler’s former head of military intelligence for the eastern front.

Interestingly, similar shenanigans were happening in Australia, where discarded former Nazi spies and war criminals were slipped easily into the stream of mass immigration using false identities. With CIA assistance, Australia’s own spy agency ASIO recruited some to report on communist influence in ethnic communities here.

The story is taken up in TRAITORS by Frank Walker, How Australia and its Allies Betrayed our Anzacs and Let Japanese War Criminals Go Free.

The book doesn’t really come up with actual traitors but rather outlines: Australia’s poor record of prosecution of Nazi war criminals and resisting extradition of suspected ex Nazi Croatians, Slovenians and Hungarians to face justice in their homelands; and the mixed success of trials of Japanese war criminals.

An extraordinary Anglo-American top secret mission, Operation Paperclip, was sent behind enemy lines in late 1944 to recruit Nazi scientists at war’s end. T Force agents were boffins themselves and had to convince the targeted 9,000 scientists, engineers and technicians to defect or be taken. Germans had made astounding breakthroughs in jet engines, V2 rockets, biological weapons and superior tanks, knowledge which the Americans were desperate to apply.

Famous V2 scientist Werner Von Braun, who had worked at the Dora concentration camp near Buchenwald, initially fled to Austria but then handed himself into the Americans with his blueprints. Eventually his Nazi record was wiped clean and with other colleagues put to work on the US missile program.

Meantime in southern Manchuria in 1943 near Harbin, Japanese scientists were conducting biological weapons experiments on Allied prisoners of war in a facility known as Unit 731. Fanatical General Ishii Shiro oversaw research operations there using pathogens for anthrax, plague and other diseases, and across SE Asia in conquered territories. Human specimens were treated as animal laboratory material and disposed of by succumbing to the experimental effect or by execution and autopsy.

At the Tokyo War Crime Trials, the big question was whether supreme wartime authority Emperor Hirohito, ‘who still commanded God-like reverence’, should face trial. Our Doc Evatt said yes but General MacArthur said no, as he reckoned you would need a million troops to control the population. Finally, from the A list of high level Japanese suspects, seven were sentenced to death and sixteen received life sentences, but with clemencies and commutations the longest sentence served was 13 years.

Ishii Shiro was given immunity from prosecution as his knowledge of germ warfare was useful to the Americans and possibly used by them in the Korean War. Other Unit 731 scientists formed a veterans group called Seikonkai (association of refined spirits) and built a memorial to Unit 731 in a Tokyo cemetery.

Many other leading Japanese political and military leaders went unpunished, including Nobusuke Kishi, overseer of the brutal Japanese occupation of Manchukuo in N.E. China. The US thought he would be a good pro-American, anti-communist Japanese leader. By 1957 he was prime minister and later succeeded by his grandson Shinzo Abe.

Walker states that Japan seems intent on wiping out the history of its WW2 atrocities and war crimes, deliberately excluded from school textbooks, and public discussion of them taboo – the complete opposite of Germany.

Somewhat at odds with Fairweather, Walker concludes in final chapter The Hunt Never Ends, that justice in Germany’s Nazi reckoning is ongoing, with ageing concentration camp guards brought to trial following the conviction of John Demjanuk in 2011 for his role in Sobibor camp. Legal criteria for prosecution were finally eased and other cases followed. The Central Office of the State Justice Administrations for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes claimed to have tracked down and prosecuted 7000 war criminals since its inception in 1958.

The Trading with the Enemy chapter recounts collaborationist profiteering by US and German industrialists participating in the Nazi regime’s war and genocide machines.

In the 1930s IBM’s punch card technology was used to identify and track down Jews. During the war it’s German subsidiary Dehomag set up and maintained the same technology in each concentration camp, creating codes for prisoner types – and their fate, to distinguish between those who had been over-worked or gassed to death. IBM head Thomas Watson had cultivated his top level Nazi contacts, was personally decorated by Hitler for his service, and received one percent commission on Nazi business profits.

The German industrial war machine co-opted chemical and pharmaceutical conglomerate IG Farben, steel giant Krupp and many other firms, but the story of Topf & Sons is quintessentially shocking. Founded in 1878 at Erfurt, near Weimar, it made furnaces for breweries and later incinerators for crematoria.

In 1938 a business opportunity arose nearby with the new Buchenwald concentration camp. The Topf engineer came up with a better version of an agricultural oven used for incineration of animal carcasses. By 1941 Topf & Sons had installed and were maintaining their brand ovens in concentration camps at Dachau, Mauthausen, Gusen and Auschwitz. The firm constantly improved the efficiency and size of its ovens. It continued in business after the war. The languid post war comeuppance of its key executives was typical, as was their denial of any culpability.

To conclude is difficult. Human capacity for cruelty is always with us, but plumbs astonishing depths under the perverse mass psychology created in authoritarian, hierarchical group situations throughout world history. These two books are useful contributions to our understanding of literally world-shattering events still in living memory.

Lest we forget our history.